Nuclear fusion gets a boost from a controversial debunked experiment

A 1989 experiment offered the promise of nuclear fusion without the need for high temperatures, but this “cold fusion” was quickly debunked. Now, some of the techniques involved have been resurrected in a new experiment that could actually improve efforts to achieve practical fusion power

By Alex Wilkins

20 August 2025

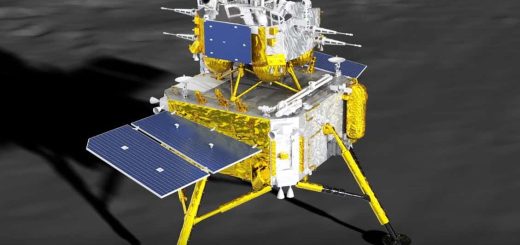

The Thunderbird nuclear fusion reactor

Berlinguette Group, UBC

Cold fusion, one of the most notorious blunders in science, is making a return – of sorts. Scientists have resurrected an experiment that was once claimed to show room-temperature nuclear fusion, offering the tantalising possibility of producing energy via the same mechanism as within in the sun, but without the need for enormous heat. While the original idea was thoroughly debunked, this latest version shows a way to boost levels of fusion, even if it can’t yet produce useful amounts of energy.

Nuclear fusion is a process in which atomic nuclei are forced together at extreme temperatures and pressures, merging them and releasing energy as a result. While this takes place naturally within stars like our sun, replicating the process on Earth to use as a power source has proved incredibly difficult, and despite plans for a commercial fusion reactor first being proposed in the 1950s, we have yet to build one that can reliably produce more energy than it consumes.

Read more

'Dark photon' theory of light aims to tear up a century of physics

In 1989, it seemed like that was about to change. Two chemists at the University of Utah, Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, claimed to have demonstrated nuclear fusion occurring at room temperature in a tabletop experiment, consisting of a rod of palladium submerged in water infused with neutron-rich deuterium and zapped with an electrical current. This process appeared to produce spikes of excess heat beyond what was predicted from simple chemical reactions, which Pons and Fleischmann took as a signal that nuclear fusion was occurring at a significant rate.

The experiment, which quickly earned the name cold fusion, drew intense interest as it showed an alternative and easier path to cheap, clean energy production than conventional hot fusion. But with multiple researchers around the world failing to replicate the excess heat observations, the idea was dead in the water by the end of that year.

Now, Curtis Berlinguette at the University of British Columbia in Canada and his colleagues have built a tabletop particle accelerator inspired by, but fundamentally different from, Pons and Fleischmann’s original work.